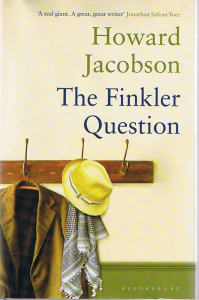

by Howard Jacobson

UK. 384 pages. 2010.

“He should have seen it coming. His life had been one mishap after another. So he should have been prepared for this one.”

“He should have seen it coming. His life had been one mishap after another. So he should have been prepared for this one.”

Julian Treslove, a professionally unspectacular and disappointed BBC worker, and Sam Finkler, a popular Jewish philosopher, writer and television personality, are old school friends. Despite a prickly relationship and very different lives, they’ve never quite lost touch with each other – or with their former teacher, Libor Sevick, a Czechoslovakian always more concerned with the wider world than with exam results.

Now, both Libor and Finkler are recently widowed, and with Treslove, his chequered and unsuccessful record with women rendering him an honorary third widower, they dine at Libor’s grand, central London apartment.

It’s a sweetly painful evening of reminiscence in which all three remove themselves to a time before they had loved and lost; a time before they had fathered children, before the devastation of separations, before they had prized anything greatly enough to fear the loss of it. Better, perhaps, to go through life without knowing happiness at all because that way you had less to mourn? Treslove finds he has tears enough for the unbearable sadness of both his friends’ losses.

And it’s that very evening, at exactly 11:30pm, as Treslove hesitates a moment outside the window of the oldest violin dealer in the country as he walks home, that he is attacked. After this, his whole sense of who and what he is will slowly and ineluctably change.

“The Finkler Question” is a scorching story of exclusion and belonging, justice and love, ageing, wisdom and humanity. Funny, furious, unflinching, this extraordinary novel shows one of our finest writers at his brilliant best. (Book product description from Bloomsbury)

About the Author:

An award-winning writer and broadcaster, Howard Jacobson was born in Manchester, brought up in Prestwich and was educated at Stand Grammar School in Whitefield, and Downing College, Cambridge, where he studied under F. R. Leavis. He lectured for three years at the University of Sydney before returning to teach at Selwyn College, Cambridge. His novels include The Mighty Walzer (winner of the Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize), Kalooki Nights (longlisted for the Man Booker Prize) and, most recently, the highly acclaimed The Act of Love. Howard Jacobson lives in London. (Summary pulled from the Man Booker Prize site)

An award-winning writer and broadcaster, Howard Jacobson was born in Manchester, brought up in Prestwich and was educated at Stand Grammar School in Whitefield, and Downing College, Cambridge, where he studied under F. R. Leavis. He lectured for three years at the University of Sydney before returning to teach at Selwyn College, Cambridge. His novels include The Mighty Walzer (winner of the Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize), Kalooki Nights (longlisted for the Man Booker Prize) and, most recently, the highly acclaimed The Act of Love. Howard Jacobson lives in London. (Summary pulled from the Man Booker Prize site)

Order this book

When you order this book on Amazon.com or Amazon.de, a percentage of the price is goes right back into site maintenance and development! Go ahead—buy your books and support TheBookerTea.com.

Touted, after winning this year’s Booker Prize for being an exploration of British Jewishness, the appeal to my Jewish roots was strong, particularly because Jacobson is a writer I had read and liked before. He had been very funny and provocative. In this book, despite many rave reviews which I read just before writing this comment, the book was not a hit for me. I didn’t trust the story itself. I didn’t buy into the “crime” against Julian Treslove, the non-Jew in a threesome of two Jewish friends. Julian, rather failed and frustrated in his present life as an impersonator, thinks he wants to be a Jew. Finkler, a character familiar to me as an ASHamed Jew with anti-Israeli feelings (like my own), is a bit too much a posturing media personality without much depth while the third friend, Libor, a Hungarian widower, is almost one dimensional for me as the Jewish refugee who sees things from a Jewish refugee’s fears and sentimentality.

The three characters could have made a more interesting triangle with some less repetitive and more interesting delving into their psyches, but it isn’t that sort of book. I found I wanted something more.

Granted The Finkler Question is often very funny and filled with some provoking ideas. I imagine it elicited some interesting talk at the Berlin Booker Tea. Some books are much better read as part of a group and this, for me, is certainly one of them. I was sorry not to be in Berlin to hear the thoughts of others.

A short discourse on Finkler (ha!):

I had many stages of response as I read the book. It was easy to read, seamlessly written, but for a long time I wouldn’t say I liked it. Ultimately, I did but with some caveats. To me, the most formidable stumbling block is that two of the three central male characters–Finkler and Treslove—lack a third dimension. Certainly there are people out there like these two, but the men rarely seemed to live and breathe. I’m one of those callow readers who wishes, at some point, however late in the book, to feel concern, empathy for the main character. Not so doable with the strawman Treslove. So there remained a hollowness at the center for me.

The humor, much vaunted by the Booker judges and condemned as heavy-handed by at least one prominent critic, was somewhat more subtle than the press seems to have it. The parts that were the funniest were not the one-liners but the absurd situations people engage in (like Finkler’s taking up with the “ASHamed” Jews), the tendentious fantasies they nurture (Treslove’s waif-women needing to be saved), the way Treslove, especially, so unfailingly misperceives the people he meets. People misperceive each other relentlessly and destructively or they don’t even recognize a need to try to breach the gap. The history of the world.

The examination of ant-Semitism in British society was something new for me to think about. I hadn’t given much thought to anti-Semitism as having much purchase there. I mean here not just a fringe phenomenon, but as suggested in the book, something relatively acceptable, woven throughout history, still transmitted today, and almost institutionalized in some forms. The ASHamed Jews are reacting to a climate in which Israel is presented as a bogeymen, a violent abuser. The author seems to suggest that the consistent condemnation in the British media of Israel over Palestine on apparently intellectual and political grounds is both a manifestation of an enduring, primitive anti-Semitism and a catalyst for anti-Semitic acts carried out by various groups and individuals looking for a place to lay blame for their discontents and a way to strike out. At the same time Jacobson doesn’t wish to deny the intellectual and moral inconsistency of some of Israel’s policies and actions–a condition inherent to all nations, as Tyler Finkler points out in her writings. He has made a deft job of sketching the scene.

I’m sorry that during the group meeting we didn’t get around to discussing the political theater piece attended by Treslove, Finkler, and Hephzibah in the later part of the book. It turns out that this play is a thinly veiled reference to a piece by the British playwright Caryl Churchill, which stirred controversy about what it means or doesn’t mean to criticize Israel—the same issues outlined in the “ASHamed Jews” strand of the book. For those interested, two links here, the first to the Wikipedia entry on Churchill’s piece Seven Jewish Children and the second to Howard Jacobson’s column in the Independent about the play and the response to it. The Guardian, which quite liked the play, has a version available for download.

Forgot the links related to the Churchill play:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seven_Jewish_Children

http://www.independent.co.uk/opinion/commentators/howard-jacobson/howard-jacobson-letrsquos-see-the-criticism-of-israel-for-what-it-really-is-1624827.html

A very interesting take on a book I had commented on briefly. Thanks for the links which I would have missed.

I have been involved with so much Israeli discourse, pro/con, for years now and must choose sides beyond saying the situation is complicated. It is. But at some moment one must be able to see injustice and dishonesty and betrayal of an idea… and the reality. I must strongly condemn what is going on in Israel, including the mentality that has made the Holocaust a justification for indecent behavior, even when many Israelis were never touched by its atrocities.

In following the link to the above piece by Howard Jacobson I better understand how far apart I am from his thinking. We are at real odds over some basics and I’m not sure if its because he is a British Jew and I an American Jew. I disagree with how he sees the situation , and why his ASHamed Jews and all his characters miss being whole people for me, and instead are stereotypes that even miss the basic essence of who they characterize.

I am sorry THIS is the book that was chosen to speak to the place of Jews in English culture. This was the Booker moment and I think it failed to find the story most worthy of characterizing the real depths of the fear and conflict, pride and discomfort that must affect British Jews, as it does their American counterparts.

In the group discussion, I spoke to how this story resonated with my experience in American identity politics. While many have already commented that Jacobson brings a distinctly English experience to the subject matter, I myself thought his characterizations of the struggles of people pulled in to inherited (versus chosen) identities was spot on. There are indeed comical characters in our progressive movements — people who shame the more nuanced voices with their oversimplification because they are fill-in-the-blank by birth. The ASHamed Jews of this story — well, I have met these people live and in person in movement groups. As the character Tyler clarifies in the novel, these characters place certain locales (cities, states, nations, continents) on a pedestal and disallow the usual failures of any group of people or nation-state. Whether Africa for African Americans or Israel for Jews, the ideals that these places are expected to live up to become cop-outs for all sides. In the novel, Jacobson uses the debate among the ASHamed Jews regarding the group’s name and whether it is or is not to be abbreviated to further illustrate this very well. Although we see only Finkler’s point of view, we get that the room is hot with contention, acrimony, and pretentiousness, as well as bits of wisdom on how they are to position themselves in this debate. We get through Finkler, too, the part that we movement people do not speak of publicly but often endure/navigate: the enormous role that ego/positioning plays in our groups. We may not like Finkler, but he is as real as his real-life counterparts. That there are others more eloquent, ethical, and charged about Israel does not negate that.

The more I muse on the last, say, fifth of the book, I get the sense that Jacobson’s story at this point was heavily informed by his responses to ongoing storms in the British media about events in Gaza, including the Churchill play and the surrounding response. At least one person, Denise, noted a disappointment with the last part of the book. It seems that current events jerked the book off what could’ve been a somewhat different path at the end. Maybe not a whole lot different, but I think there is an effect.

So this book continues to stay with me. I guess that means it’s got something. Just read this piece on NPR Web site, including some thoughts from the author.

http://www.npr.org/2010/12/06/131848784/howard-jacobson-meet-the-jewish-jane-austen